Facing North

In our nascent, pioneering stage of cold climate viticulture, many familiar with Vitis vinifera ask, ‘How does the character of this northern landscape distinguish these hybridized grapes?’ A landscape hosts an immense holistic network which plays a major role in this boundless notion of « Terroir ». These workings cannot be reduced to the sum of their component parts, especially when we do not yet possess the yardsticks to measure even a fraction of what is going on right before our eyes let alone beyond our vision.

Terroir emphasizes so much more: the cardinal direction of the slope and how the sun and the wind land and move across the vines. Terroir includes ambient yeasts, the native pollen, and the countless fauna occupying the air above and the soil below. We who work the land have our place among these forces to influence terroir yet the wine is created by more than the work of the grower.

Terroir is the recurring effects of climate, and of course separate but very much related, the dynamic vicissitudes of this season’s weather sweeping over a given year. Even so, in all due respect, all of these pieces even fail to capture the numinous powers at play -ready to reveal themselves any time one pauses to marvel or reflect upon the wondrous coöperation surrounding us and moving trough us.

No matter the fine print of one’s faith, we share more than whatever details divide us -especially when there is clearly a Providence beyond any measure we could fathom -a generous wisdom that patiently awaits our curiosity to express itself and engage us in all these wondrous workings well beyond our grasp.

The teeming earth beneath our feet

Isn’t it remarkable how one looking down might assume the soil beneath the grass is uniform as far as the horizon? Instead the shift from one soil to the next is a puzzle we work out patiently over time as we measure and mind all the pockets in every parcel to note their character and adjust their handling in turn. Humbled, we are reminded terroir is not merely a matter of soil types but the interplay of nature and nurture.

Our predominant soil profile is Antigo Silt Loam, Wisconsin’s state soil -a soil so special that it even has its own song. In terms of viticulture it is an ideal combination for water retention, nutrition and drainage thanks to this corner of Wisconsin resting at the end of a glacial plain leaving 16 to 18 inches of silt loam on average with even more in some parts, all above a gravel base. As these soils are neutral, measuring 6.5 to 7 pH, grapes thrive in good health. These soils shape into slopes with good aspect for drainage as well as casting fog and encouraging courses for breezes to pass over and through. Atop a hill, we get a lot of air movement.

These are the soils we first planted to in 1993 and they have been managed to be even healthier over time. We add a lot of organic matter to the soil through foliar feeding, root feeding, and soil supplements to help the plant’s uptake of nutrients through the roots. Regular additions of molasses foster healthy microbial activity among the mycorrhizal networks that encourage micronutrient uptake as well as act as an interface among the vines to communicate and respond better and quicker to whatever it encounters.

We regularly submit tissue samples at every bloom and at veraison to adjust appropriately. After years of effective tissue analysis we have moved on to sap analysis for even greater measurement. For this we send plant material to a lab in Holland to determine the nutrients taken up by the plant -a pioneering endeavor providing insights never known until this new technology was developed.

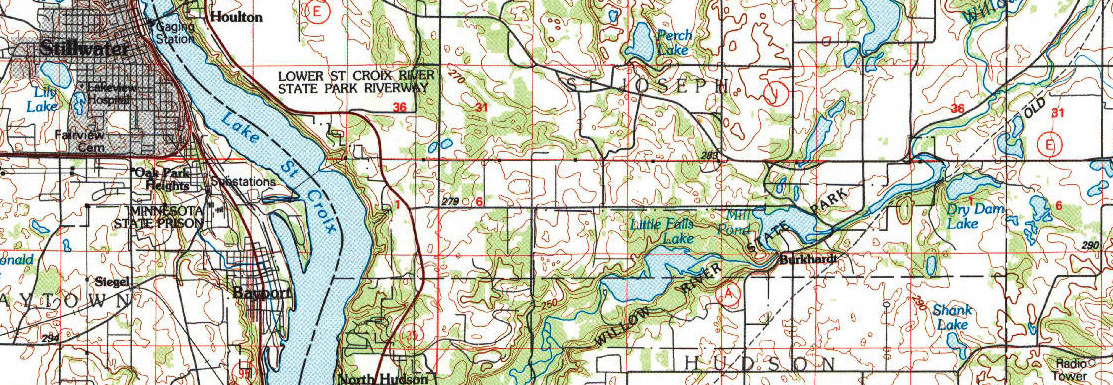

Trout Brook topography

A vineyard’s altitude and its subtle variations over the acres it drapes can determine the varied slopes, their cardinal direction, how vines face the sun throughout the day, how they cast rainfall, and permit fog to roll on down the lowlands and over a greater scale how soils will wash down over the centuries to change exposure.

Living on the land a farmer cannot help but notice how each of these behave differently and how each should be handled with different care thereby proving terroir is an interplay of people and place -that farming is a relationship with the land.

Our various blocks possess distinct characteristics and depending on each grape variety and depending on the air flow and the angle of the sun, we train each canopy a little differently. In some cases leaf thinning while in others raising the vines. Exposing the fruit might benefit some cultivars while others might not favor direct light. The elevation and aspect of the slope can determine how direct the sunlight land and this is yet another consideration.

At agricultural conferences we are often asked how our vineyards remain bountiful year on year -especially when our vines carry more fruit than many other grape growers. Even so, our fruit fills out and clusters reach a highly desired phenolic ripeness. Much of this is vigilant vineyard management but the aspect should not be overlooked.

Most of the prized vineyards of Europe face East and due South to appreciate the greatest hours of sunshine. Here in the North country, orchardists and vignerons agree that planting on southerly slopes runs a risk of early flowering which could subject these to harmful frosts after flowering and thereby poor fruit set -if the crop is not lost altogether. Northern, cold hardy varieties are also especially vigorous which means northerly slopes curve some of this earnest energy. These are some of the reasons we face North. Learn more about our cold hardy grape varieties to appreciate what each brings to the table.